My friend Snerx is an interesting guy. He is one of the few people in my life who displays a rare quality that I consider important for friendship—being a schizoid asshole with a lot of compassion. His name is one of the most French-sounding names in existence, and yet he is enthusiastically anti-French, which I suppose makes him even more canonically French.

A few weeks ago, I attended a lecture he gave on his Discord server about Alien Axiology, during which he read excerpts from his book on the topic, with interjected questions (mostly from me) and discussion. I found the experience to be generative.

άξιος (axios): value, worth, deserving

axiology: the systematic study of values

alien axiology: the axiology of all species, including terrestrial, extra-terrestrial, and non-terrestrial beings

Snerx’s native intellectual languages are meta-ethics and philosophy, whereas mine are mathematics and biology. We can both speak in computation with decent fluency, though in this particular language, his taxemes tend to be more formal and mine tend to be more pragmatic.

In this post, I will pull out some specific passages from the paragraphs in the chapter and elaborate on some of the aspects that were worthy of further consideration. I suggest that you either (1) read the linked pages before proceeding, and/or (2) have them open alongside this post.

Throughout this piece, I will place select text from the chapter in block quotes as I’ve done below.

The opening paragraph of the chapter sets the stage:

Here is a universal-like account of the resource constraints, psychology, and game theory of all species across all worlds – a convergent axiological framework by which all intelligent life in the universe trends towards. I argue for this to help flesh out cross-disciplinary understandings of how value systems develop and to draw laws in the study of axiology with which we can make accurate predictions of intelligences we have yet to encounter.

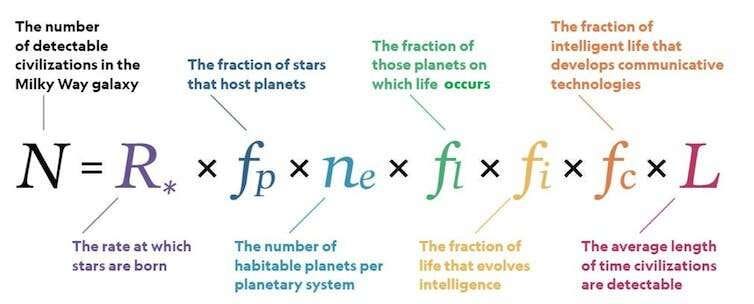

The Drake Equation as controlled opposition

The chapter continues as follows.

If you personally don’t trust the growing piles of video footage being released, I think it doesn’t matter because you shouldn’t need photographic evidence to have good reason to believe other people exist outside your specific bubble of experience. You do not have to be like the European colonists discovering the new world – you have no obligation to act incredulous upon learning that you can travel in a straight line and run into more people (yes, even if that line points straight up).

One of the first things Snerx stated during the lecture was his belief that the Drake equation is controlled opposition, in that it is a reasonable-sounding formulation with just enough seeming scientific legitimacy to be well-considered.

I’ll admit I had not considered this angle before, but after some time, I must agree there are a couple of points that support this notion.

The Drake equation uses variables that may be fundamentally unknowable.

Fraction of planets that develop life (f_l): This requires understanding abiogenesis, which we’ve never observed. With only one example (Earth), we can’t distinguish between life being inevitable given the right conditions versus being a virtually impossible accident.

Fraction of life that develops intelligence (f_i): Intelligence itself is relatively poorly defined, and tends to be anthropocentric. We don’t even particularly understand consciousness or how intelligence emerges from matter. More fundamentally, we can’t know if human-like technological intelligence is an inevitable evolutionary outcome or a bizarre fluke, à la Boltzmann brains.

Fraction that develops detectable technology (f_c): This assumes technological civilizations follow paths similar to ours. Advanced civilizations might deliberately avoid detection, use technologies we can’t conceive of, or exist in forms we wouldn’t recognize as technological.

Civilization Lifespan (L): This requires predicting the future behavior and survival of intelligent species we’ve never encountered, based on technologies and challenges we can't imagine.

Governments and academia are more interested in promoting metrizable standards that eschew the need for empirical investigation.

Perverse Incentive Structures: The Drake equation provides a mathematically respectable framework that allows researchers to publish papers, secure funding, and build careers around The Search For Extraterrestrial Life (SETI) without making testable claims. It’s safer to promote theoretically rigorous mathematical speculation than to seriously interrogate the presence of Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena (UAP).

Risk Aversion: Relatedly, both government and academic institutions are inherently attitudinally conservative, especially in the 21st century. The Drake equation allows them to engage with the alien question in a way that won’t trigger ridicule, controversy, or substantial intellectual scrutiny.

Funding and Resource Allocation: This matters because many university departments and government agencies feel pressured to provide justifiable frameworks to bureaucratic processes to gain funding for astrobiology and astrophysics programs.

In this vein, the equation gives an illusion of scientific tractability to questions that may be fundamentally beyond empirical resolution with our current epistemological frameworks.

None of these proposed reasons is particularly conspiratorial, either.

Of course, it is also possible that the Drake equation serves as a pressure release valve for public curiosity about alien life—to manage both public enthusiasm and potential panic by making the possibility of alien life seem more distant and unlikely than the dictates of reality. But this adds malicious intention where it is not needed.

Major institutions central to American society routinely shape public discourse through selective information presentation and statistical manipulation. Institutional narrative management—whether through emphasis, omission, or methodological choices—is a well-established feature of how complex topics are presented to the public. The same institutional dynamics that shape discourse around other sensitive topics, from health policy to national security, likely influence how the search for extraterrestrial life is framed and funded.

The reason I found this noteworthy is that it reframes the entire axiological discussion away from speculating about hypothetical alien value systems, and toward the analysis of universal axiology that would need to navigate brutal evolutionary pressures toward a stable, cooperative meta-ethics.

Snerx ends the following paragraph with a similar conclusion.

With the evidence we have, there is so far a 100% likelihood that there are 20 to 80 billion advanced civilizations in the Milky Way that are habitable, and until we get to explore/observe another habitable planet, that likelihood will stay 100%. You can claim this is bad statistical reasoning due to low sample size all you want, but unless you’re willing to wager real money on it, then shut up and know your place. There are many ways to contact me and we can arrange a fair bet on whether any other planets within 100 light-years of us host non-human people.

Homoplasy in exo- and xenobiology via modularity

Moving forward, Snerx starts speaking in ways that turn me on.

Convergent evolution (homoplasy) … selects for otherwise complex biological structures across independent evolutionary tracks. For example, eyes have independently evolved over a 100 different times in myriad environments. This is because light-sensing cells and organs are almost universally advantageous, with the only exceptions being deep cave systems or underground tunnels that don’t get any sunlight. Given enough time, complex organs like eyes are expected to evolve as an adaptation of any complex life form.

As a kind-of-well-trained scientist, what I immediately focus on from this paragraph is that even when cave-dwelling species “lose” their eyes as described, they’re typically losing only the terminal expression of an enormously complex, multi-stage developmental program—the final photoreceptive structures themselves—while retaining the vast majority of the underlying genetic and cellular machinery.

This machinery spans multiple biological scales simultaneously.

At the transcriptional level, master regulatory genes continue to be expressed and maintained even in eyeless cave fish and bats, because these same genes control other developmental processes beyond vision.

The morphogenetic signaling pathways that pattern developing eye fields remain intact because they’re reused throughout embryonic development for limb formation, neural patterning, and organ positioning.

The cellular infrastructure for photo-reception persists largely unchanged even under conditions where light is not a selective pressure: the basic architecture of photoreceptor cells, their synaptic connectivity patterns, and the neural circuits that would process visual information remain genetically encoded and developmentally accessible.

Such cave species even maintain the molecular machinery for synthesizing rhodopsin photopigments, the ion channels that would convert photon detection into electrical signals.

The reason this conserved machinery matters is that complex organs like eyes represent enormous metabolic investments, from constant protein turnover in photoreceptors to the neural processing power needed for image analysis.

Evolution has therefore favored a modular approach: maintaining the complete developmental toolkit in an accessible but dormant state, allowing populations to rapidly deploy these expensive systems only when environmental conditions justify the cost.

Animals can afford to down-regulate their visual systems in light-absent environments because the complete machinery remains ready-on-demand. When the presence of light becomes pertinent selection pressure again, the system can be reactivated within relatively few generations rather than requiring millions of years to re-evolve from scratch.

Snerx extends this logic to predict convergent traits in intelligent alien life.

This is something we can generalize as a law in exobiology – that by the time you reach higher intelligence, you will have already gone through a long evolutionary track that has selected for universal advantages like vision. Just the same, we can expect most highly intelligent life to be humanoid, since walking upright uses the most minimal number of limbs for locomotion and conserves the most energy – energy that is needed for metabolically demanding pathways like cognition.

Humans are renowned not for maximum speed, strength, or sensory acuity, but for exceptional endurance and the ability to maintain moderate performance across multiple domains for extended periods.

This principle represents a similar form of metabolic modularity.

Rather than investing heavily in any single expensive capability, humans evolved systems that can be efficiently scaled up or down based on immediate demands. We’ve evolved what could be called an “adaptive durability,” making high-performance biological capabilities easily accessible when urgently needed, without requiring their permanent expression across entire populations.

The same principles of modular construction would apply to alien evolution, but more importantly, the underlying efficiency likely extends beyond physiology into behavioral and social systems.

Homoplasy in exo- and xenoethology via modularity

Thus, just as complex organs maintain conserved developmental machinery, cooperative behaviors likely rely on conserved psychological and cultural machinery that can be activated or suppressed based on environmental demands.

Culture itself becomes a downstream expression of cooperative animal biology that can scale from small-group coordination to complex multi-species cooperation without rebuilding the entire framework from scratch.

This is how Snerx continues the argument into generalized alien ethology.

The same line of reasoning leads one to expect a similar convergent phenomenon in exoethology. Behaviors trend towards the social and the cooperative as a species spreads across more environments and becomes more intelligent. From the eusocial insects like ants and bees all the way to humans, the larger the population and the more environments the populations spread into, the more social and cooperative the species needs to be with members of its own kind, and others, in order to maintain the expansion.

The key insight is that cooperation, like vision or endurance, follows well-worn methods and sequences of extensibility. Species don’t need to maintain maximum cooperative capacity at all times, which would be metabolically overtaxing, and rife with parasitism, and therefore maladaptive in resource-scarce environments.

Our cultural systems have the capacity to regulate (though lately, they’ve been doing it quite badly, and in a possibly self-terminating manner) everything from intimate pair bonding to global naval shipping systems.

For alien species, this same principle suggests that any civilization capable of interstellar expansion has already solved the scalability problem of cooperation in this way. They must possess modular & extensible systems that can efficiently coordinate behavior across vast distances, time scales, and potentially different species, while conserving resources when such coordination isn’t immediately necessary.

The more intelligent a species is (primates, cetaceans, and so on), the more complex their social/cooperative behaviors become (e.g., dolphins play culture-specific games)

The Кардашёва/Kardashev scale defines civilization’s capacity for harvesting and deploying energy from stellar radiation. However, based on the reasoning presented here, for these definitions to become more complete, they must also address energy harnessing in terms of the axiological infrastructure necessary to coordinate such massive undertakings.

I’ve come up with somewhat expanded definitions of Kardashev II & III types.

A Kardashev Type II civilization can directly consume a single star’s energy, most likely through the use of a Dyson sphere. A Type II axiology must be able to synchronize activities across multiple worlds within a given solar system, which involves:

Generational Transmission: Cooperative systems that can maintain coordination across generational timescales, where individual participants may never see project completion.

Cross-Planetary Protocols: Mediums of exchange that function across radically different planetary environments with highly dissimilar resource contexts and electrochemical foundations.

Transhumanoid Integration: Scalable systems for incorporating differing cognitive architectures, both inter-humanoid and intra-humanoid, into cooperative frameworks.

Distributed Decision-Making: Frameworks allowing autonomous subsystems within the solar system to act cooperatively without constant central oversight.

A Kardashev Type III civilization can directly consume the energy from every star within a galaxy. A Type III axiology must retain the same cooperative modules from the Type II axiology and also operate according to:

Lightspeed Communication Constraints: Systems that maintain coherence despite communication delays of thousands of years between galactic regions.

Cultural Drift Management: Preventing breakdown or cooperative modules and sub-modules as civilizations separated by vast distances inevitably develop different values and priorities.

Conflict Resolution at Scale: Mediating disputes between civilizations that may be more alien to each other than humans are to bacteria.

Resource Allocation Algorithms: Distributing galactic resources to maximize potential energy and minimize kinetic friction among millions of different species with alien needs and values.

Importantly, these sociocultural capacities represent the prerequisites for advanced space civilization; on their own, they don’t resolve a fundamental asymmetry problem untouched so far. Even if Type II and III civilizations have solved cooperation among equals, the question remains: how do they treat civilizations that haven’t yet developed equivalent capabilities?

The 14th Amendment may doom us all

At this point, Snerx devotes some time to the following question: if a Type II or Type III civilization were the demonstrate a robust exoethology as described, it may lead to several overlapping adverse consequences for terrestrials.

That premise is, of course, baked into many science fiction novels and movies—in that a much more advanced society invades Earth, inducing horrors ranging from mass extermination, to mass psychosis, to mass enslavement. However, I endeavor to give these concerns a slightly more serious (and hopefully realistic) consideration.

The general measure of the survival of our species matters and I think the game theory is quite clear: if you are a more intelligent species and you exploit that intelligence to dominate less intelligent species around you, then what is to stop a more intelligent species from doing the same to you when you show up? And in and infitnite univerise, there is always someone more intelligent. Nash equilibrium rests at the refusal to abuse your power, lest you invite others to do the same back to you.

This equilibrium argument, however compelling in theory, skips several critical steps. The claim that intelligent species will refrain from exploiting power differentials because they fear retaliation from even more advanced species assumes a kind of universal rational actor model; moreover, it presupposes a sort of Rawlsian “blank axiological canvas” and waves away potential challenges through an “appeal to inevitability via infinity.” Since the aim here is to discover an axiology with substantial empirical grounding, rather than treat the argument-via-homoplasy as a tidy thought experiment, it would be more valuable to examine clear, embodied instances where this non-abusive equilibrium was actually achieved.

In my opinion, Earth’s clearest example comes from Anglo civilization, which demonstrates both the promise and vulnerability of ethical evolution. This civilization progressed from participating in the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th century to leading global abolition movements within just two centuries—a remarkably rapid ethical transformation that supports the convergent cooperation thesis. Moreover, in the 20th century, it established some of the most comprehensive and effective wildlife preservation programs across the globe, stretching into even the most insipid and challenging of ecologies.

Yet, this same civilization now faces potential civilizational failure not through external conquest but through internal dissolution. Post-WWII Anglo societies have systematically dismantled their own cooperative infrastructure through mass migration policies that fracture social cohesion, bureaucratic expansion that strangles adaptive capacity, and the destruction of non-corporate cultural and familial structures that historically maintained cooperative norms.

It would be strange to think the species that initiates galactic hyper-war would also win it since we just said they don’t understand basic things relevant to general intelligence like ethics or game theory. There is no probable world in which a species that dumb wins repeatedly against most intelligent opponents. I’m not even sure what disagreeing with this would look like since it feels like saying a <1,000 Elo chess player would somehow consistently win against a >2,000 Elo player. It just wouldn’t happen.

This illustrates how a “<1000 Elo” civilization might indeed “defeat a >2000 Elo” one: not through superior strategy but by exploiting the higher civilization’s cooperative vulnerabilities. Modern Chinese civilization demonstrates this dynamic through systematic information warfare, economic infiltration, and exploitation of Western openness and legal constraints that the Chinese system doesn’t reciprocate. Modern Indian civilization operates via a similar playbook.

Snerx, in a later paragraph, makes a similar declaration about ethology that arises from the stated Nash equilibrium as it relates to resource harvesting.

An understanding of your existence as a competitor in an environment of finite resources does not require you to consciously suffer something like the angst of living under post-industrial capitalism until it totally alienates you from participating in it. This kind of suffering is not a requirement for a ‘true understanding’ that our world is one of finite resource, so it does not follow a priori that competing for finite resources requires any negatively associated attitudes or behaviors. Instead, the more we understand about the finiteness of resource in an infinitely consumable market, the better we are at adjudicating a balance between the two, and this balance seems to have no limits to scale.

In present times, there is a common attitude that presents industrial capitalism as an unalloyed good: a system that optimally balances resource extraction with cooperative benefit. However, the technocratic neoliberalism that has emerged from this framework appears to be dissolving the very cultural foundations that made such cooperation possible, creating (and even encouraging) precisely the ‘negatively associated attitudes’ that bad actors exploit.

This critique might sound like standard anti-capitalist rhetoric, but I’m not stupid, so it’s not. The issue isn’t capitalism per se, but the loss of defensive mechanisms that historically regulated it. Once again, strangely (or maybe not so strangely) enough, Anglo-Christian civilization seemed to have actually developed a sophisticated balance between energy harvesting and cooperative management—integrating extraction, competition, charity, and social cohesion through variable and diffuse expression across multiple institutional levels.

The breakdown occurred when this modular system was replaced by a singular technocratic framework that assumed pure rational optimization could replace cultural immune systems. Thus, the claim “this balance seems to have no limits to scale” is demonstrably false, according to the most immediate empirical evidence we have of modern civilization’s arc.

Whether the Western world can develop new defensive modules to reverse its cooperative overextension remains an open question. This would require at minimum: (1) institutional capture resistance preventing bad actors from corrupting collaborative systems for energy extraction, (2) cultural preservation mechanisms that maintain cooperative norms while allowing adaptive change, (3) information warfare defense that can distinguish legitimate discourse from systematic manipulation, and (4) demographic stability protocols that prevent rapid social changes from overwhelming intergenerational transmission of operational wisdom.

Defensive extensible modules as the missing galactic ingredient

Finally, returning to the fundamentals of homoplasy, the operational components of a civilizational axiology with sufficient defensive mechanisms will almost definitely be modular and ordered along a complex developmental holon. These might include:

For a Type II axiology,

Quantum-encrypted communication networks across the solar system to prevent infiltration of decision-making processes

Distributed consensus mechanisms that can’t be compromised by corrupting a single communication hub

Cultural authentication protocols that verify the origin and integrity of information flowing between worlds

Decentralized energy distribution preventing single points of failure in Dyson sphere networks

Automated defense swarms protecting critical infrastructure like stellar collectors or orbital habitats

Economic compartmentalization where compromised colonies can be isolated without collapsing the entire stellar economy

Cognitive compatibility screening for entities seeking to join the civilization

Gradual integration protocols that prevent rapid demographic shifts that could destabilize cooperative norms

Cultural preservation zones maintaining core cooperative values while allowing controlled diversity

For a Type III axiology,

Civilizational quarantine protocols that can isolate bad-actor species without genocidal war

Distributed governance networks where no single region can be captured to control the whole galaxy

Cultural redundancy systems ensuring core cooperative values are preserved across multiple independent civilizations

Stellar engineering restrictions preventing hostile civilizations from weaponizing stars or black holes

Galactic traffic control managing faster-than-light travel to prevent surprise attacks

Resource allocation algorithms that can rapidly shift away from compromised regions

Ethical compatibility matrices for evaluating which civilizations can safely interact

Buffer zone maintenance keeping incompatible ethical systems at safe distances

Conversion or rehabilitation protocols for transforming exploitative civilizations rather than destroying them

As of right now, I’m not well-versed enough to consider how these would all fit together within a modular evolutionary framework. If my readers have more experience or interest in the particularities of some of these notions, I invite them to share with me.

Dunking on utilitarians is one of the highest ethical goods

The rest of the chapter spends a lot of time elaborating on several philosophical arguments and counter-arguments that I’m not interested in re-hashing.

I do enjoy a nice evisceration of utilitarianism—it’s not a coincidence that it is the most common framework used to bypass the memetic defenses of collectives—and Snerx does not disappoint.

That said, the more substantial set of points to address is located here:

If ethics is to be useful to us, or do any work whatsoever in describing the good and evil in the world, it would be quite the problem to find that no normative system can meaningfully describe the other normative systems as good or evil in a way those other systems couldn’t easily counter with their own descriptions. I am not saying normative ethics is relative because they disagree on what is good or evil or that they become meaningless if more than one framework exists – I am saying that as a comparative analysis between normative frameworks, given any scenario to which the frameworks return conflicting answers, it becomes clear that we must instead rely on external non-normative systems to conduct the analysis, and that is a problem, e.g., does utilitarianism, or virtue theory, or Kantianism, or contract theory, or any other framework actually get us a good resolution, or anything desirable at all, in some particular dilemma? This is an empirical question and should have an easy empirical answer.

But even if we had empirical data, empirical data is not unto itself a normative framework, and someone must assess the data to determine if it gives us good or evil results. I believe the problem re-inscribes itself here.

To generalize the point: even if we develop instruments of measurement sophisticated enough to identify normative consistency at levels of specificity heretofore unreached, the observer effect tells us that the act of empirical observation itself changes the ethical state being measured.

Remember from earlier, it was established that eusocial hive minds are an unlikely convergent solution for a universal axiology. Part of the reason for this is that eusocial systems cannot accommodate external observation without fundamentally altering their cooperative structure. The moment you introduce outside evaluation criteria, the hive mind cannot maintain its deterministic roles while simultaneously optimizing for observer-defined metrics of cooperation.

Snerx proposes a solution that outlines a meta-normative consistency framework that, at its core, represents an ambitious extension of basic Aristotelian virtue ethics.

With this as the guiding principle, it is possible to abandon particular normative ethics in favor of compatibilist meta-ethics where we derive accounts of agents and their acts based on consistency alone. This solves the earlier problems in alien axiology by allowing for a convergent theory of values, as well as solving the problem of frameworks not being able to self-justify and the issue of comparative analysis.

[…]

From this we attain a meta-ethics we can guarantee is consistent with the meta-ethical architectures of all possible foreign ethics for all possible species of higher intelligence since it is a meta-ethics of general consistency.

This intuitively strikes me as the correct approach because it solves the observer problem by focusing on structural relationships rather than content evaluation. The goal here is to validate the convergent evolution thesis while avoiding the trap of anthropocentric projection. We don’t need aliens to develop human-like virtues, and the aliens should not require this of us either; only coherent systems that maintain logical integrity under mutual observation.

Crucially, consistency as presented doesn’t depend on specific cognitive structures or evolutionary histories. Two alien species with radically different neurological frameworks could both achieve internal consistency while developing completely different value systems. They could then interface with each other by recognizing and respecting each other’s coherent frameworks, even without sharing specific values. This creates a universal language of civilization based not on shared moral content, but on shared commitment to coherence across as many scales as possible.

For practical interstellar relations, this means that first contact protocols wouldn’t focus on determining species-specific moral intuitions, but rather on establishing whether they demonstrate consistent principles that can interface with other consistent frameworks, including whichever ones humans deploy. Several species could maintain completely different value systems while still achieving stable cooperation, as long as both systems are internally coherent and externally compatible.

Now, are there any terrestrial examples of a successful implementation of this type of compatibilist meta-ethical framework?

Without getting into too many details, I would say yes, and they include:

Medieval Hanseatic League Trade Networks

The Ottoman Millet System

The Swiss Confederation

The Chinese Millennium-Long Tributary System

Indian Ocean Trading Networks & the Modern ASEAN Model

The Mughal Empire’s Religious Pluralism (under Akbar)

Post-WWII NATO Coordination

Unfortunately, while these examples showcase remarkable human ingenuity in developing consistency-based cooperation, none achieved truly global scale. NATO comes closest to planetary reach, but even it represents only a fraction of Earth’s civilizations. This suggests that while the consistency framework clearly works at regional scales across diverse value systems, scaling it to planetary levels remains a great challenge.

The cosmic forest is dark because of professionalism, not phobia.

Where does all of this analysis leave us?

From a high-level view, my response to Snerx has essentially been an exercise in re-formulating the Fermi paradox through the lens of homplasic axiology.

The Fermi paradox represents the contradiction between the high probability of extraterrestrial civilizations existing—based on our understanding of the universe’s scale and stellar abundance—and the lack of observable evidence for their existence. In simpler terms: given the vastness of the universe and the estimated number of stars, intelligent alien life should be relatively common. However, we have no concrete proof of their existence, leading to the question: "Where is everybody?”

Liu Cixin posits the Dark Forest Hypothesis as a solution to this paradox: a cosmic sociology wherein the universe is filled with Kardashev Type II and III civilizations, but they remain hidden from each other, fearing mutual annihilation. It’s an elegantly paranoid hypothesis that claims that hyper-advanced civilizations would essentially behave like impulsive teenagers with intergalactic nuclear weapons, striking first and asking questions never.

I believe Snerx’s framework suggests a different answer to the darkness of the universe. Namely, the universe appears as a dark forest not because all the predators are hiding from each other, but because civilizations advanced enough to be detectable and dominionistic have also developed sophisticated protocols for managing contact with less developed species.

A type of benevolent galactic chauvinism.

Advanced civilizations might maintain communication networks and cooperative relationships that are simply invisible to us, the same way our global internet infrastructure would be incomprehensible to a Paleolithic jungle tribe, even if they could somehow detect the radio waves emanating from deep ocean submarines.

Following this reasoning, the Great Filter isn’t merely the development of weapons capable of planetary destruction and species subjugation. It also includes the development of consistent meta-ethical frameworks that can coordinate behavior across cosmic scales. The civilizations that make it to Kardashev Type III are probably, in fact, the most ruthless. More importantly, however, they’re the most coherent, too.

And if that’s the case, then the question isn’t, “Where is everybody?” but rather, “How and how soon can we demonstrate the axiological readiness to join the conversation?”

(Shot out to

and for taking a look at early drafts and offering some feedback)

As below, so above.